The Wonder and Weirdness of Postmodernism

Introducing the Postmodern Worldview

Growing Up in the Jesus Path – Part Five

Postmodern art is a style of contemporary art created from about 1960 onwards. It gives us a glimpse into the postmodern era and is best understood by looking at what it sought to contradict: the perceived traditional values and conservative point of view of the modern artists who were active between 1870 and 1970. This Warhol is an ironic commentary about mass media’s obsession with celebrity culture.

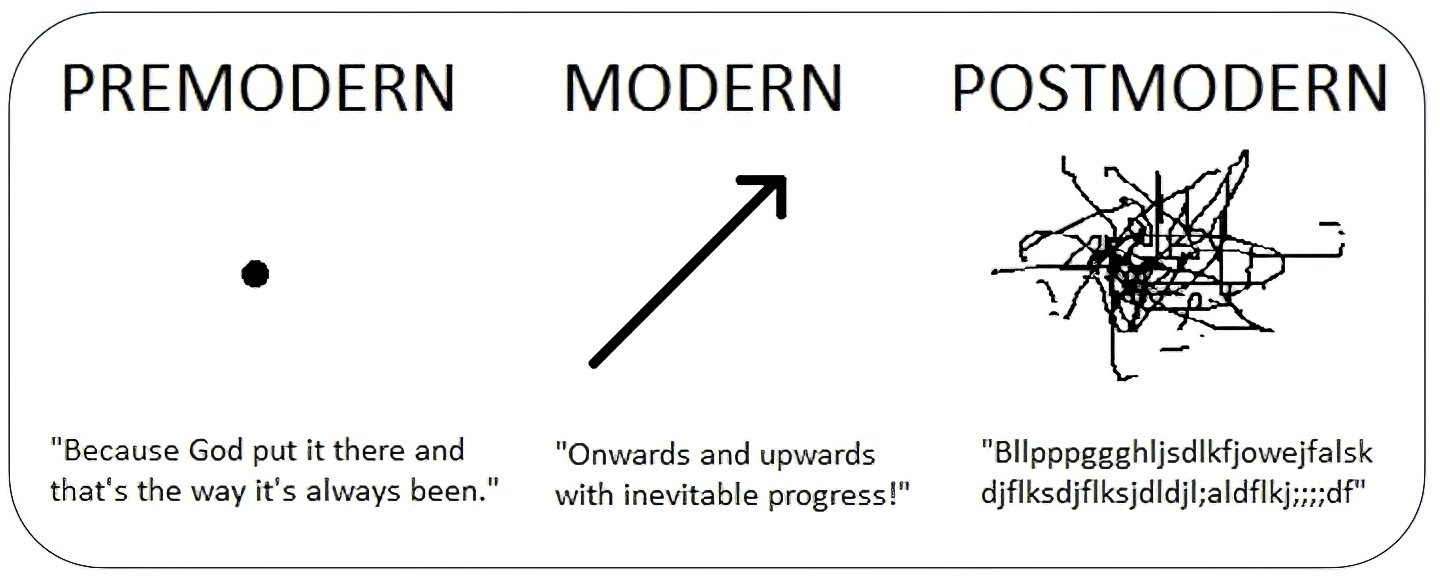

Postmodernism is a general, much-debated term applied to many fields such as literature, art, philosophy, architecture, fiction, and cultural and literary criticism. It is a reaction to the modern idea that objective science can explain reality. The postmodern station in life began around 150 years ago and became most noticeable in North America during the 1960s.

Postmodernism understands that reality is not just something objective but that our minds also play a part in constructing what we think of as reality. It is skeptical of any universal claims or ultimate principles that claim to be true for everything. It makes the universal truth claim that there are no universal truth claims!

Coming into prominence with the Enlightenment, modern consciousness focused on questioning the foundations of past knowledge. Postmodern viewpoints challenge whether we can know much of anything at all. The modernist bumper sticker advises, “Question Authority.” The postmodern bumper sticker says, “Question Reality.”

Modernism says there is absolute truth. Postmodernism says we construct our own truth. Modernism says that what is important are observable facts and logic. Postmodernism says that what is important are feelings and experience.

Modernism limits itself to scientific exploration, while some actively seek out other spiritual paths for their own enrichment in postmodernism. One begins to see commonalities among the world’s religions, not just differences. All ways are seen as equally valid. Because of this, there is a tendency to despise any kind of hierarchy that says anything is better than something else.

Postmodernism rejects the premise of integralism that there really are identifiable stages of development, considering this elitism. The postmodern altitude, rather than seeing everything in black and white terms, is more comfortable with shades of gray.

Postmodern philosophy says that absolute truth cannot be discovered at all, neither through reason nor tradition. In the extreme, there is no objective meaning, only subjective meaning, the meaning one brings to anything. History is seen as merely various fictional interpretations. The postmodern worldview was cleverly summed up in an editorial cartoon that showed a boy sitting on Santa’s lap. Santa is saying to him, “And have you been a good boy this year?” The boy replies, “It depends on what good means.” Behind him, a boy thinks, “Sixty-five percent of my peers say I’m good.” A girl in the line says, “That’s a private matter between my family and me.” The last boy says, “It’s time to move on to the real issue: what I want.”

Postmodernists say such things as, “There are no facts, only interpretations,” “Nobody tells me what to do,” “Your truth is as good as my truth,” “I have no limits,” and the foundation of them all—“We create our own reality.” Sometimes there is a deep agony over the way things seem. Postmodernists see so much diversity that they can’t see any unity. Postmodernists value community, consensus, and diversity. The rights of minorities are upheld so that a majority does not crush the minority.

Looking through the postmodern lens, one sees that there is more to life than clear thinking and being rational. Enchantment has returned. It again embraces the mystical and numinous, which was lost in the modern rational stage. Networks and connections are often developed between others who share a similar interest in spirituality. Talks, workshops, and seminars on various aspects of human potential and spirituality are popular.

Meditation, prayer, and the inner life are explored with new fascination. However, in its rush to embrace mystery, it does not always distinguish mystical experience from magical thinking. One is an authentic connection to what is real, the other is a fantasy. This new appreciation of the mystical sometimes moves into the fantastical. The New Age reigns!

The traditional level sees authority and God as something external. Moving away from the Bible, churches, and religious leaders as authorities, there is a move to see one’s own experience as authoritative for one’s own life. Individuals at the postmodern station in life tend to think more about God being everywhere and in everyone.

Postmodernity is seen in ecological awareness, political correctness, diversity movements, universal human rights, multiculturalism, humanistic psychology, liberation theology, and the human potential movement.

The Postmodern stage comprises an estimated 10% of the world population and 20% in the United States.

GROWING UP — from Spiral Dynamics by David Goebal

Postmodern Church

Postmodern religious thought was originally a reaction against mainstream Protestant liberalism. The cold idea of a religion that just “thinks” finally gave way to opening the door to dimensions that were warmer than reason alone. Reason was not discarded, but it no longer reigned as the only way to “know.” Rationalism alone does not work anymore in the postmodern church.

Spiritual exploration can give us a sense of connectedness with the cosmos.

While the modern level is filled with scientific exploration, the postmodern one is filled with spiritual exploration. Science said that seeing is believing. Postmodernism comes along and says that believing is seeing. There is a move from facts and logic to feelings and personal experience. This move is not always navigated well, and some postmodern religion under the “New Age” rubric includes elements of prerational, deficient magic, and post-rational mysticism.

There is a move from only the God of the Bible to considering the God of other religious paths. Jesus really does look like a feminist in his day, and he spoke out for all the religiously, politically, and socially oppressed.

For many in this stage, nature becomes their church. They prefer to leave behind the confining structure and institution for something more open and freer. Many communities that might not be considered “church” serve as spiritual community in this stage, such as yoga studios, home groups, circling communities, or other alternative forms.

The Bible

Marcus Borg is an outstanding model of the progressive, postmodern, Christian theologian. Although a prominent member of the Jesus Seminar, he takes the Bible seriously. Concerning the Bible, Borg says, “Over the past century, an older way of reading the Bible has ceased to be persuasive for millions of people, and thus one of the most imperative needs in our time is a way of reading the Bible anew.” He describes the traditional stage understanding of the Bible as literalistic, doctrinal, moralistic, patriarchal, exclusive, and after-life oriented. He sees the Bible as a combination of history and nonliteral linguist art he calls metaphor. In the postmodern stage, one can see that the biblical stories can be true without having to be literally and factually true.

Borg describes this as “a way of seeing the Bible (and the Christian tradition as a whole): historical, metaphorical, and sacramental. And a way of seeing the Christian life: relational and transformational.”

God

While agreeing, in general, with John Spong’s deconstructed, modern-stage theology, Borg warms things up spiritually in postmodern fashion by focusing on a relationship with God that is transforming. Concerning God, Borg says, “God is not a supernatural being separate from the universe; rather God (the sacred Spirit) is a nonmaterial layer or level or dimension of reality all around us. God is more than the universe, yet the universe is in God. Thus, in a spatial sense, God is not ‘somewhere else’ but ‘right here.’”

Borg holds three central convictions about God: (1) God is real; (2) the Christian life is about entering into a relationship with God as known in Jesus Christ; (3) that relationship can—and will—change your life.

Panentheism reigns in the postmodern church as a way of understanding God. It is briefly described in Acts 17:28, where Paul in Athens quotes from a local poet who says, “In him we live and move and have our being.” This indicates that such an idea of God existed in the first-century Christian church.

Theism is the view of God that sees God as separate from creation. Pantheism is the belief that God is everything and every part of creation. Panentheism offers a third way of viewing God with an emphasis on the middle syllable “en.” God is in everything and everything is in God. God is in creation but is also greater than creation. I believe panentheism is the most advanced way of thinking about the Infinite Face of God that is compatible with both postmodernism and integralism. It describes the Infinite Face of God-Beyond-Us.

Jesus

Jesus may or may not be as central to the postmodern church as it is for those like postmodernist Borg and myself as an Integral Christian. New Thought churches wrestle with this, and some settle it by not talking about Jesus much at all, or only along with Buddha and Krishna. Without more profound insight evolving from the traditional view, Jesus may be seen as divisive, excluding those who do not follow him. A post-postmodern view or integral view understands that Jesus loves and welcomes everyone.

At the extreme postmodern level talking about Jesus can be almost taboo. I know of Unity churches that have decided not to talk about Jesus because this appeared to exclude Buddhists and others from the spiritual path. Christians looking through the postmodern lens are less likely to believe that the baby Jesus was God come down from heaven in bodily form and more likely to believe that Jesus grew up to be a wonderful person who realized and manifested his own divinity in a breakthrough way.

For those who remain open to Jesus, there can be an understanding that Jesus and Christ are two different descriptors. Jesus refers to the historical person who taught and lived in first-century Galilee and is present with us now in a non-physical subtle energy body. Jesus revealed an awareness of God that might be called the “Christ consciousness.” The word “Christ” then becomes a description of the unity of divine, human, and material reality, as well as the “spirit-breath-awakened-consciousness” that not only Jesus had, but is already present, in everyone waiting to be released.

Jesus is not only a great teacher and human being, but there is something about divine-human spirit that comes through him in an extraordinary way. At this point, if one still considers a relationship with Jesus a vital part of the spiritual life as Borg does, the Living Jesus will also be seen as personal and incredibly loving presence, inclusive of everyone.

Justice issues come alive in both the Old and New Testaments for the postmodern church. The Jesus of the postmodern church is a liberator. The prophets are valued, and Jesus’ parables are seen in the context of subverting the day’s oppressive social/political structures. Borg understands Jesus as a Jewish mystic, healer, wisdom teacher, social prophet, and movement initiator. He reveals a warm, important Jesus who is full of life, saying:

“The Bible paints a picture of Jesus by making extraordinary claims about him. He is one with God and shares in the power of authority of God. He is the revelation of God. He is also the revelation of “the way,” not only in John but also in the synoptics. He is the bread of life who satisfies the deepest hunger of human beings and the light shining in the darkness who brings enlightenment. He lifts us out of death into life. He is the World and Wisdom of God embodied in a human life. He is the disclosure of what a life full of God—a life filled with the Spirit—looks like. This is who Jesus is for us as Christians. Some modern Christians have been uncomfortable with these claims because they seem to partake of Christian triumphalism. But for Christians these claims should not be watered down. For us as Christians, Jesus is not less than this—he is all of this. And we can say, ‘This is who Jesus is for us’ without also saying, ‘And God is known only in Jesus.’”

As the richness and limitations of postmodernism are particularly relevant right now, I will continue to describe the postmodern stage of Christianity in my next writing.